We can think of our experience with stress as a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum we are relaxed and not stressed at all, at the other end we experience crisis. And then there are stages in between. We can use the spectrum to assess our situation. That way our interventions can be fast and precise and match our current needs. It can also become easier to recognize a crisis and understand that it is time to get more help. The only downside is that we need some experience with stress and crisis to be able to identify the important signs of it.

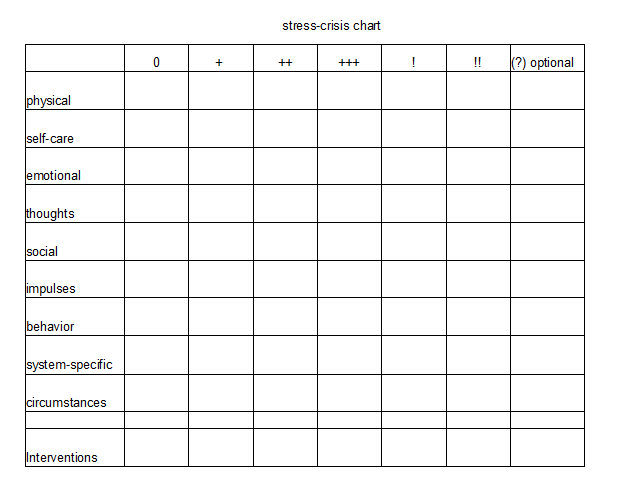

In this exercise we will not look at triggered moments of stress that pass quickly and instead look at stress levels that are consistent over a period of days. A day of high stress is no problem but when it becomes a week we need to pay attention. We start by dividing our spectrum into different levels of distress. A graphic that can often be found online uses 5 levels: excelling, thriving, surviving, struggling and crisis. These were made for people with average mental health and I don’t think it is enough for what we need. We use 6 levels: being relaxed and grounded, mild stress, medium stress, high stress, very high stress and crisis. In case you have very specific things happening within your system, like a tendency for non-epileptic seizures that are connected to other conditions than stress alone, you might want to add an extra level for that. Anything outside of stress that has caused hospitalization in the past might be worth looking into in addition to stress levels. We start our chart by making a column for each level we want to look at. You can color-code your levels or use numbers or symbols like we are doing it here.

Areas of experience

In the rows we will look at different areas of our experience. It needs time to reflect and remember what a certain level of stress is usually like. We don’t have to finish our chart in a day. It makes sense to work with it continually and add new understanding over time. People change. We will give you examples of details you could watch out for but everyone will have to figure out what is important and what is not.

Areas of experience we might want to include:

- physical: awareness of body sensation or the lack of it, pain, specific sensations (tightness, restlessness, struggle to breathe etc), amount of movement impulses, sensory sensitivities/numbing/functioning, sense of temperature, control over movements, kind of stimulation/numbing we seek, levels of symptoms in chronic illnesses, muscle tension, self-harm, parts working against physical safety etc

- self-care: amounts we eat and drink, how regularly we eat and drink, sense of hunger/thirst, effort made to provide good food and drink, amount we sleep/insomnia, amount of nightmares, time of the day we sleep, regular hygiene, keeping up with usual hygiene routine/ letting things slip or reducing less necessary elements, keeping up with necessary chores, amnesia that prevents self-care, inner conflict that prevents self-care etc

- emotional: emotions most often felt, intensity of emotion, emotional numbing, differences of emotions between parts, conflicting emotions within the system, emotional flashbacks/being stuck in time, ability to express emotions, specific emotions like despair, overwhelm or extreme shame, ability to contain emotions, emotional suffering or a curious lack of it when it would be appropriate etc

- thoughts: topics, repetitive thoughts, cycling thoughts, (in)ability to think about other things, memories feeling real right now, ability to contain memories and not get flooded, empty head/no thoughts, thinking to distract from feeling, inner conflicts, inner disagreements, ability to think about the future, suicidal thoughts, black and white thinking, old rules, trauma beliefs and patterns etc

- social interactions: seeking company, withdrawing, hiding, aggressive behavior towards others, superficial contact/masking, level of mistrust, conflict, ability to keep up with interpersonal responsibilities, social coping like submission and appeasement behavior, passivity, etc.

- behavior: ability to follow routines/keep up with responsibilities, finding no joy in things that usually bring joy, stopping or starting certain behaviors, acting against own interests or values, reduced activity, frantic activity, inability to stop being active at all times, forgetting important tasks, out-of-control behavior, unexplained behavior etc

- impulses: impulsive behavior, impulses to act against our goals or values, impulses to self-destruct, aggressive impulses, unusual impulses like wanting to contact people who hurt us, impulses taking over while emotions/thoughts cannot be accessed etc

- system-specific: fronting parts, dormancy, sensitivity to triggers, certain parts struggling, recurrent patterns of distress within single parts or between certain parts, level of amnesia, level of cooperation, flooding or unwanted blending, parts stuck in memories, conflicting needs or goals, amount of dysregulated parts, re-enactments, etc

- circumstances: Work load, free time, responsibilities, unusual events, level of support available, access to resources, contact with difficult people, exposure to triggers, unsafe environment, extreme situations etc.

We can always add whatever we notice about our individual situation. These are just examples. It is often easier to start with the ends of the spectrum and work our way towards the middle. Make sure not to dive too deep into a memory of crisis when you try to identify the signs and symptoms that define it. The more we can listen to other parts while doing this, the more useful information we can collect. It is ok to leave gaps in areas where we are not aware of our experience yet. There is plenty of time to fill that in later.

Interventions

We should end up with a collection of information that helps us to compare our current experience with the chart and find the level of distress we are in. To make this chart more useful, we need to add interventions that fit the level of distress. This will be very individual and depend on the help that is available to you. When we are relaxed we usually don’t need an intervention. In a crisis, we need hospitalization to stay safe and survive. Everything in between is up to us. We can add our personal interventions underneath the corresponding column.

Usually mild distress only needs interventions like a higher focus on self-care and measures to reduce stress. When higher levels of stress become persistent, we might have to take a break. That can include sick days or asking someone to take over a few of our responsibilities. We need to free up capacity to sort through everything that is going on and find a solution. Even higher levels of distress will require support from outside. We need to contact helpers and allow them to support us. High distress will require frequent contact with helpers and professionals. When we are close to hitting a crisis it is normal to talk to people from the support network every day to make sure we are safe. It is important to write down our own interventions that go beyond contact with helpers for every level of distress because we all have different abilities and resources and differ in how much experience we have with high stress and how to cope with it. People who are only learning how to cope will need a higher level of support a lot earlier than those who have a sad routine with crisis.

Difficulties

We will sometimes experience situations where we use our coping skills and realize that they aren’t as effective as they should be. The moment we stop using them, we are back on the persistent level of distress we were experiencing and it is not going down. We probably failed to realize that we are actually on a higher level of distress by now and a different set of interventions is needed. Dissociation and numbing can make it very hard to assess where we are at. That is why paying so much attention to the level of numbing, not feeling, not thinking, not acting, not connecting, not suffering, is so important. The lack of a normal response needs to be taken just as seriously as if the symptom was present in an extreme form. Numbing is an extreme expression. To evaluate our situation, we need a clear picture that includes many areas of experience and functioning. We cannot look at our ability to keep up with work because functioning can be selective and our ability to work with our head doesn’t say anything about our emotional state. By adapting the original CBT exercise to our special needs and including dissociation and work with parts, we can make it more useful.

The chart is meant to be used regularly. If possible, we should go through it at least once a week, even if we feel like we are doing well. We can’t rely on our feelings. We need to check. Then we can find out where on the spectrum we see ourselves and what kind of intervention, if any, would be needed. That way we can balance ourselves before we ever hit a true crisis. It can be terribly hard to sense how we are doing. I have begged psychiatrists to explain to me how to know when I am in crisis and they have always looked at me like I am crazy for not knowing. With dissociation, this really is hard. But having a chart to help us assess our situation helps.

(This exercise is known by a bunch of different names and is taught in a bunch of similar ways. I have seen it used in CBT but I couldn’t figure out who invented it or even how it was originally called. Our version is a personal interpretation intended to make it more useful for DID and the reality of living with DID)

More about making a safety plan

Leave a Reply