This post is based on „The polyvagal theory“ by Stephen Porges. The book describes a mostly scientific theory about the nervous system, specifically different parts of the vagus nerve and how it is related to stress and social interaction. The details on the anatomical side are boring and difficult. So we will butcher it, take the bones out of the theory and offer you a filet about the parts that are relevant for cPTSD. Anyone who is actually interested in physiology should read the book instead.

In a nutshell

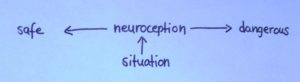

Neuroception: We notice a lot more than ever enters our conscious awareness. According to theory our brain combines this information to sorts every situation into one of two simple categories: safe or dangerous.

The trauma brain tends to identify things as dangerous more often, even if they are not.

Neuroception

Response circuits

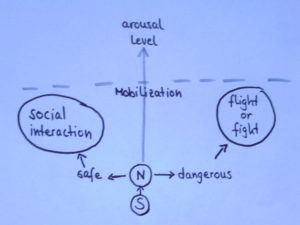

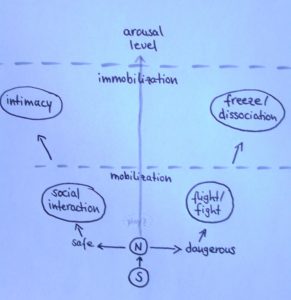

When something new happens we respond with an increase in physiological arousal levels. Depending on whether neuroception considers a situation safe or dangerous this is expressed differently.

The first arousal system the body enters is mobilization.

In a safe situation, mobilization shows in social interaction, communication and connection (ventral vagus).

If the situation is considered dangerous the mobilization system that gets activated is flight or fight (sympathetic arousal).

mobilisation system

With a further increase in arousal level we enter a different response system, immobilization (dorsal vagus).

In a safe situation that takes social interaction to an intimate level.

If the situation is considered unsafe, immobilization shows in the freeze response, that is dissociation.

polyvagal theory

[The theory hints at a hybrid between the mobilization systems flight/fight and socializing: play. It combines mild „fight“ with social interaction, while the ventral vagus is dominant. It can be especially difficult for trauma patients, but also a valuable approach for therapy]

Change can only happen when the first step, the choice whether something is safe or not, is repeated and leads to a different conclusion. That’s what we do with grounding.

What does all that mean for us?

People need to feel safe. That is even more true for traumatized people.

Relationships: Relational regulation is one of the strongest grounding techniques out there (for PTSD, not always true for BPD). If you feel connected to someone you are less likely to dissociate in their presence. Unusual dissociation during therapy might even be an indicator of a disturbance in the therapeutic relationship. A calm tone of voice, friendly facial expression and familiar movements can help you to feel safe with someone.

Places: You need a safe home. And you should remove triggers from it. Your therapy setting should also feel safe to you, especially when you go to a clinic for longer treatment. A good trauma clinic will provide a room that you don’t have to share with anyone else and give you the possibility to lock that room. A conflict-based ward is not for you.

Therapy: Trauma therapy usually starts with creating safety, inside and outside. That includes breaking contact with abusers. Your T will also introduce you to the imagery of the Safe Place early on. Being safe and feeling safe are at the foundation of successful trauma therapy. You don’t stand a chance to heal without safety.

DID SystemWork: It’s important for every part of you to feel safe. Committing to a non-violent approach in SystemWork will help you to make your system a fear-free zone. That includes giving up punishment and blame as relationship tools.

This is the most solid practical result of the research on the vagus nerve: Feeling safe will reduce your symptoms. And you can work yourself into exhaustion using Skills, if you don’t feel safe, you won’t calm down. The proper order to get out of a difficult situation is this:

safety, orientation&grounding, soothing (which can include relational regulation)

If you remember one thing about the polyvagal theory, let it be this: safety first!

If you like theories, go ahead an compare this one with the window of tolerance and color-code the response circuits!

Going deeper

If you want to follow me into the realm of interesting ideas, we need to look at the actual physiology a little bit. I will try to make it comprehensible, at the cost of physiological accuracy, so please don’t take it literally.

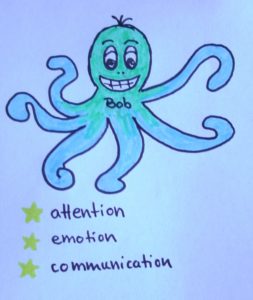

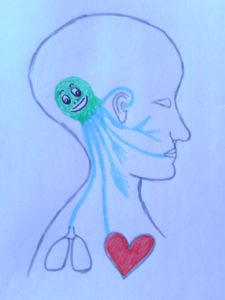

meet Bob

The complex act of calming down needs a certain part of the nervous system to be active. It involves the vagus nerve and especially the ventral part of the vagus nerve, that I will call Bob. Bob is like an octopus in your brain, with his arms reaching into different parts of the body. Those parts are:

- heart

- breathing

- throat&swallowing

- sucking

- speaking

- facial expression

- head turning

- hearing differences in noises

Bob in action

Calming is an active effort. Bob needs to work hard for that, keeping up “muscle” tension. When Bob lets go, we experience activation. That is natural and good, as long as it is not a constant state. His personal talents are attention, emotion and communication. If you have noticed that you can’t communicate properly when stressed or that you turn numb and can’t focus, that is a lack of Bob-action. Scared people don’t communicate well.

Baby Bob

Bob grows and develops best when we have secure attachment as a child. He learns from the mothers Bob, moving in attunement with her until he gets the knack of it. Insecure attachment leads to a weaker Bob, which increases the babies vulnerability to stress. It doesn’t mean that this is trauma, it just increases the vulnerability for trauma.

trauma Bob

Trauma Bob

Sexual abuse leads to an especially harmful situation. It forces us into immobilization while we are in a state of fear and mobilisation. This is a combination our nervous system can’t process and Bobs ability to keep us calm is reduced long-term. Our brain changes. There is a chance that we will develop problems with positive immobilization and enter the fear-based dissociation system in intimate situations.

Resilient Bob

Resilience describes the ability to return to the original shape after pressure was applied. It is natural that Bob will drop tension in a situation that might be dangerous. We would be sick, if that didn’t happen! The most interesting measure for our ability of self-soothing is how fast Bob picks up his work again after he got startled away. Research indicates that Traumatized Bob needs a lot longer to return to his job than Healthy Bob and he doesn’t come back as strong. More about polyvagal pendulation

Supporting Bob?

A lot more research is needed to find reliable ways to influence Bob or ‘strengthen’ his influence. Some ideas are based on the areas of the body Bob touches with his arms (see above). The influence doesn’t just go one way (brain through Bob to heart), there is also an influence going back (heart through Bob to brain). About 80% of Bobs activity goes from the body to the brain and it looks like we can make use of that.

The things I will mention now have been tested considering their value for self-soothing and emotional regulation. They have not all been researched using Bob-measures yet. But they fit into the theory.

- Exercise (isn’t that a cure-it-all? So just do it!)

- breathing exercises

- drinking a sip of water

- singing (which regulates breath, includes music and if done in a group, relational regulation)

- whistling or playing a wind instrument

- sucking (it’s better to use stim toys than cigarettes. You can find help in an autism* support store. You can also find weighted blankets there, they fit into the theory in an interesting way)

- speaking during an orientation exercise/grounding

- using facial expression on purpose, like holding a smile

- listening to music (Bob doesn’t react well to very deep and very high sounds. So maybe you shouldn’t turn on that bass or listen to high pitched screaming)

- yoga, with an integrated experience of body, breath and awareness

- safe touch eg. a massage

- …

I hope this is as interesting for you as it is for me. If you have any questions or thoughts about the theory, please feel free to comment below.

Continue reading in

*autism is showing similar Bob-related problems as PTSD: struggles in communication and connection, affect information and regulation, sensory processing, keeping eye contact, attention, sleep, overwhelm up to shutdown etc.

Hi there, I found this interesting. You sent me a good book to start with but I have lost the email. Could you tell me again.

Thanks

“the polyvagal theory in therapy” by Deb Dana

I live with a traumatized Bob. I wanted to especially thank you for that list at the end. This is a lifeline for those who deal with disassociation difficulties.