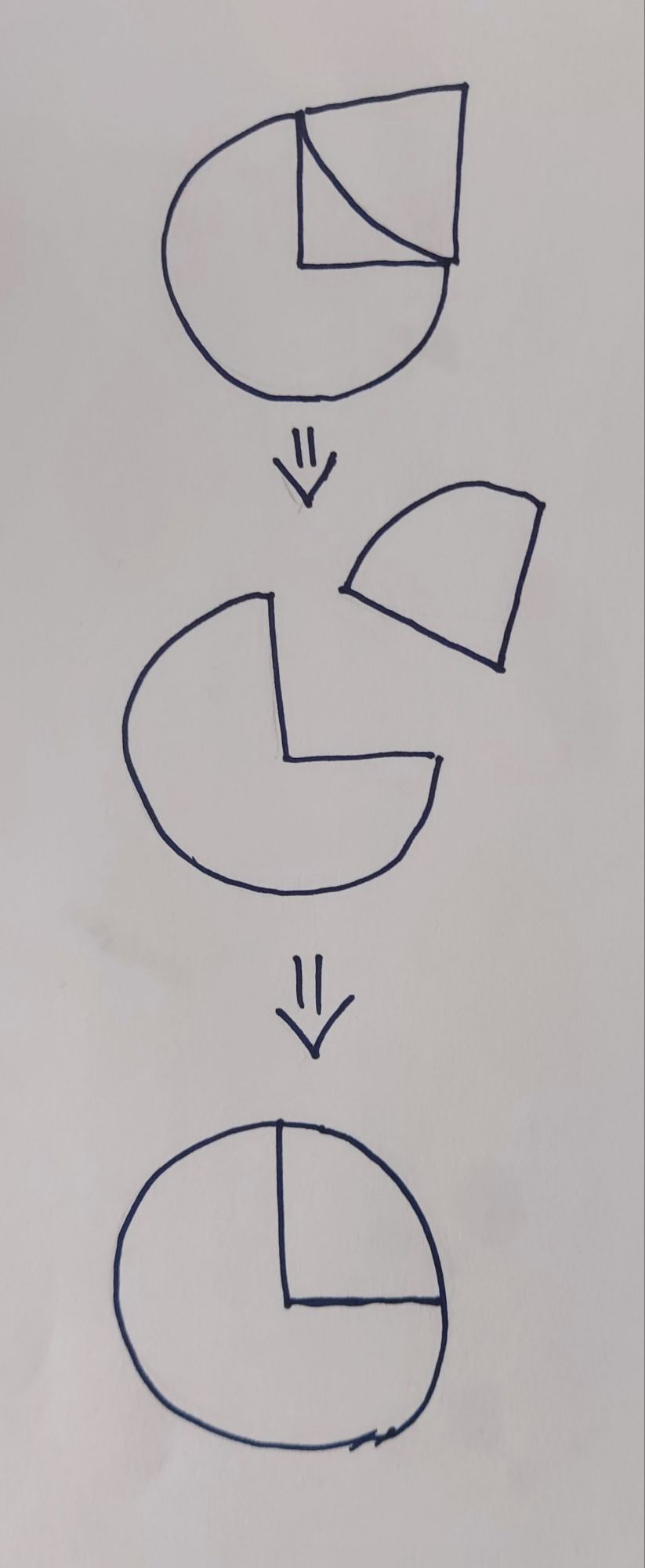

The basic idea behind trauma processing is that trauma memories were stored but they weren’t integrated into our memory properly. They never became part of our life history and when they come up, it feels like they are happening now. Completely over-simplified, we can say that something about them didn’t settle right.

The basic idea behind trauma processing is that trauma memories were stored but they weren’t integrated into our memory properly. They never became part of our life history and when they come up, it feels like they are happening now. Completely over-simplified, we can say that something about them didn’t settle right.

When we process a memory, we recall it on purpose and in a controlled setting. Bringing up a memory creates a window in which it can be influenced. The trauma therapy tools our therapists use are a form of intervention that helps to shake the memory loose from the unhelpful way it settled. It can be nudged to settle differently. Ideally, it will be stored as a scene from the past this time and the memory gets integrated into our life history. It will not somehow become a completely different memory. That is not a goal or a possibility of trauma therapy.

It is not necessary to live through the whole memory at full intensity for this process but we do have to bring things up so they are activated, otherwise the intervention will not have the impact we wanted. Things need to move out of their stuck position and get a chance to settle differently.

Research into memory and memory reconsolidation suggests that there is a time frame of a couple of hours after bringing up the memory where it can be influenced. We use some of that time for the therapy session itself. But then there is still a bit of a vulnerability afterwards where the things we experience can have an impact on how the memory will settle. That is nothing to obsess about. We probably won’t ruin the whole process by doing something that isn’t optimal. We can still make sure to protect our process from unwanted influences in the hours after the therapy session.

The helpful thought to keep in mind is that the process is not finished yet just because we took all the steps that the therapy technique offers. We shook things up really well and they still have to settle.

Possible scenarios after trauma processing

We don’t have perfect control over the memory we bring up, how it will settle again or what exactly we shake loose. When traumatic scenes are similar to others we remember, we might bring up more than this one scene we planned for. With parts involved, we might get unexpected reactions from them. And when we process trauma to a body part that has seen a lot of trauma, some of that might come up as well.

When everything goes well

Even when everything goes according to the textbook, we will usually experience that our whole being goes through some additional processes. We might notice that the memory comes up in waves that become smaller as we work on our grounding and finally calms down. Sometimes we move through changing emotions like brokenness, anger and sadness until we settle with grief about the past. The body can bring up old sensation from trauma time for a while. Sometimes there are physical responses like feeling dizzy or nauseous, we might shake, develop a bit of a fever or show other signs of the body releasing stuck trauma energy. Our whole being is busy working through the memory on different levels. That is completely normal and part of the process we want. There is no reason to try to suppress it. We can just let it happen and use our attention to follow ourselves through the different stages. It is rare to have all of that happen but some of it might.

During the trauma therapy session we usually find some kind of resolution. In EMDR that could be the positive belief we end up on. When we work with rescripting techniques, it might be a key moment that showed that we are safe now. Maybe it is a body sensation or a movement that helped us to move out of the scene. Whatever it is, we can use this resolution to support ourselves through this phase of processing. We bring up the memory of the resolution from our therapy session and hold it in our mind while we also notice the flow of experiences we go through. The resolution is the first line of resources here, together with plain grounding. We use it to support ourselves before we try other options like distractions. That way, we stay with our process instead of turning away from it. You can find more helpful activities after trauma processing by following the link.

The first encounter with a trigger after a processing session is an important moment. If everything goes well, we will notice the old trigger and it will draw our attention with more intensity than other neutral input. We will be more alert and orient towards the trigger. We will also be able to maintain awareness of the surroundings and the world today and it frames the former trigger as harmless. Sometimes this response of higher attention will stay with us and it will always happen when we encounter the former trigger. The response can also fade over time until we don’t notice the trigger as something special anymore. Both are good results. We can wait for the trigger to come up naturally in our daily life to see how well we integrated it. I have come to appreciate having this first encounter within the first week after processing but not immediately afterwards. The first encounter with a trigger is part of the process, even if it is just to get closure and a sense of new security. It tells us how well the memory settled.

Other things that can also happen

More details of the scene come up

It is not unusual for more details to be remembered while we go through the waves of memories after the session. Sometimes these details are especially painful. They were locked away from our awareness because the main memory was already too difficult to remember.When we make more room by integrating some of the memory, the details find more space in our awareness. If that happens, we remind ourselves to breathe and we get grounded. It helps to take notes and write down what comes up without trying to dive deeper into it. Instead, we keep recalling the resolution for the scene. It applies to these new details as well. We can use micro-rescripting to bring resolution to these new fragments as well. There is a chance that they will settle with the rest of the memory. If they don’t, we contain them and bring them up in our next therapy session.

Similar memories come up

When we experienced a lot of similar things, other scenes that share elements with the scene we just processed might come up. This is not a good time to work with them. We can notice what comes up, write it down, realize where the similarities are and why it is logical that this comes up right now and then we contain it. In some cases, like when we are inpatient with several therapy sessions a week, we might be able to process very similar things within a short period of time. In most regular settings, it is not possible to make use of the activation of the memory and we have to contain it again until we can take care of that. Sometimes people report that resolving one scene actually helped to resolve related scenes as well. We can’t count on that. Sometimes they are just triggered. We always choose safety first and only take the steps we are able to take. Integrating one memory is already plenty. We can mess with the process if we try to do too much at once.

New or other parts got triggered

Going through the therapy process with one part might bring other hurting parts closer to the front. In some cases, they add details to the scene that they carried. We add the memory to the puzzle and invite the parts into our resolution or use micro-rescripting to give them their own resolution. All our methods to take care of hurting child parts might be helpful to create a sense of care and safety for them. It can happen inside through imagery or on the outside by meeting their needs in small ways. If they are not oriented in the present reality yet, that can be a crucial step for them to feel better.

Generally, we document whatever memories parts bring to us and we take care of the parts the best we can in a way that moves their attention away from those memories and towards a felt sense of being seen, helped and protected. This part of the process is often centered around meeting needs related to the trauma scene. Guide for welcoming new parts

Hostile parts show up

The fact that we are moving away from the past and the abusers and towards a new life with new freedom can be difficult for some parts. They might feel attached to abusers or find a sense of safety in the past. At least they know what will happen there. Maybe they are not oriented enough to know that it is safe to move on now and they try to protect the system by sabotaging change. Parts like that can come up with considerable force after trauma processing and try to limit us or hold us back. It is not easy to work with them and if we lack experience with it, it is best to bring this to therapy quickly. It takes skill to explain why it is safe to leave old things behind, why that does not mean that we forget about the past or people of the past, how new things can be good things etc. You might get an idea of the kind of work that is needed when you look into integrating abuser-loyal parts, abuser-imitating parts or parts with a mission.

Our main goal in the time after trauma processing is to stay safe from harm. Getting hostile parts more oriented in our reality is an extra step that we might not achieve so quickly and easily. It needs integrative actions like realization on their part and those always need additional capacity. That is why it is best to discuss trauma processing with these kinds of parts before it is done. It is always a possibility that we missed something though. Our best strategy might be to separate the current process from the hostile part and explain that this was done for someone else and they can hold on to their own experience. A boundary like that is not integrative in nature but it reduces the sense of threat on both sides. Things don’t have to change for everyone at once. It is fair to allow other parts the choice of making a change and in return we respect that some parts don’t want that for themselves.

The memory doesn’t settle

Sometimes processing does not work. It is hard to tell why but studies show that it is a fact. We bring up the memory and somehow it does not shake loose and it does not settle in a more helpful way. It just gets activated and stays activated for days and we end up struggling with a flashback experience that is not easily stopped. A chaotic mix of memories, feelings, body sensations and stress responses is threatening to overwhelm us. If it does, that could be considered a retraumatization. Then our main focus becomes avoiding the overwhelm and managing the situation. To do that, we follow all our basic steps we already know. Creating safety. Orientation and Grounding. Reality-check. Discrimination. Containment.

Our first goal is to get the stress response down. It is a constant signal to our whole being that there must be a reason for being so triggered. We use our senses to create a connection to the safe world around us and take it in. And once we are more able to use our brain, we use our strongest containment and our strongest distractions to move our brain activity away from the trauma memory. We don’t have to protect the process anymore. It has already failed.

If we notice that we cannot manage the situation with our regular tools, it is time to take an emergency medication. This is the right way to handle a situation like that and not a sign of failure. The processing technique has failed. We know that it is time to intervene when we cannot gain control over our severe dissociation, when we absolutely cannot step out of re-experiencing no matter what we try, when we get seriously suicidal or know that we are losing control over self-harming behaviors.

Our first attempts to help ourselves are always to meet our needs and to gently move us towards the present. If that does not work, we add higher levels of interventions. When our tools are not effective enough, we get help. We are supposed to reach out to our therapists in these cases and we are supposed to get additional help. That is not a mistake or somehow wrong. We put all these options into our BDA plan to make sure we know what to do. The ‘After’ part of a BDA plan is very important and should never be skipped.

Thorough stabilization makes processing easier and improves the chance of success. We can avoid over-activation of old scenes if we have proper pacing for our therapy process, take our time to regulate ourselves during breaks and when we have reliable cooperation between parts. Solid preparation leads to more solid results. We don’t need new tools to manage the difficulties after trauma processing. Instead, we need all the regular tools and the better we have mastered them the safer our progress will be. Managing the things that come up can become almost natural when the way we manage our stress responses and triggered parts has become natural. Because the situation is exceptional, it will feel a bit harder than usual but we also fall back on familiar steps that feel more manageable. Especially when we decide to process trauma outside a clinic setting and without access to plenty of additional help, we need a bone-deep and rock-solid understanding of stabilization techniques. Even when things go according to plan, we might need some of that because of the way the integration process works. Most of the time, there is an additional integrative process that happens after the session. It is good to know what might happen and how to approach it.